|

Preface |

Vorwort |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

„Und jedem Anfang wohnt ein Zauber inne, der uns beschützt und der uns hilft, zu leben.“ (“And in every beginning there is something magical which protects us and helps us to live.”) |

„Und jedem Anfang wohnt ein Zauber inne, der uns beschützt und der uns hilft, zu leben.“ |

|

This wonderful and often-quoted line from Hermann Hesse's poem, Stufen (“Steps”), especially holds true for the beginning of everything, the Dào 道 (Tao) – literally translated as “the Way”, but also the way of life, the course of nature, the origin of the universe, the unity of opposites... |

So lautet eine wunderschöne viel zitierte Zeile in Hermann Hesses Gedicht Stufen. Um so mehr gilt dies für den Uranfang von allem, das Dào 道 (Tao) – wörtlich „der Weg“, auch des Lebens, der Lauf der Natur, der Ursprung des Universums, die Einheit aller Gegensätze … |

|

|

|

|

Dào: the central concept of Chinese philosophy, especially of Dàoism 道教 (Taoism). Dàoism is a (not necessarily mystical) philosophy of nature of early pre-Christian Chinese thought. It finds its condensed and well-formulated break-through in the Dàodéjīng 道德經 (Tao-Te-Ching). |

Dào: zentraler Begriff der chinesischen Philosophie, insbesondere des Dàoismus 道教 (Taoismus), einer (keineswegs nur mystischen) Naturphilosophie des vorchristlichen China, die ihren gebündelten, wohl formulierten, bahnbrechenden Ausgangspunkt im Dàodéjīng 道德經 (Tao-Te-King) findet. |

|

|

|

|

This book has been translated into more languages than any other before (except for the Bible). It is overwhelming in the way that its magnificent content is expressed and compressed. It is a poem with aphorisms and even with rhymes, combining philosophy and art from the very beginning. |

Dieses nach der Bibel meistübersetzte Buch aller Zeiten ist außergewöhnlich in seinem überwältigenden Inhalt wie auch seiner im wahrsten Sinne des Wortes „verdichteten“ Form, ist aphoristisch pointiert und größtenteils sogar gereimt, von Anfang an also Philosophie und Kunstwerk zugleich. |

|

|

|

|

The creator of this timeless work (which is both time-honored and highly modern) is Lǎozĭ 老子 (Lao Tzu), who wrote it in about 400 B.C. According to legend, he created it on request of a border guard when leaving the country. This border guard himself was immortalized in poetic form (with a grain of humor!) by Bertolt Brecht.1 Only 500 years later did this philosophy give rise to a religious sect which adorned and mystified it, thereby creating the religion of Dàoism. |

Der Schöpfer dieser zeitlosen, ebenso altehrwürdigen wie hochmodernen Schrift, Lǎozĭ 老子 (Laotse), schrieb es etwa 400 v.Chr., der Legende nach beim Verlassen des Landes auf Bitten eines Grenzwächters hin, den seinerseits Bertolt Brecht dichterisch (mit einer Prise Humor!) verewigt hat.1 Erst etwa 500 Jahre später wurde diese Philosophie aus einer Sektenbewegung heraus zusätzlich ausgeschmückt und mystifiziert, woraus der religiöse Dàoismus entstand. |

|

|

|

|

The world-wide scientific reception of the Dàodéjīng was multiplied after the surprising discovery (1973/19932) of manuscript versions which are much older than those that were known at that time. We have come 500 years closer to the original text now, and it diverges only marginally, mainly in some grammatical aspects of the text, but shows hardly any differences in content! |

Die weltweite wissenschaftliche Analyse des Dàodéjīng vervielfältigte sich seit der überraschenden Entdeckung (1973/19932) weit früherer Fassungen des Textes mehr als in 2000 Jahren zuvor, war man doch fast ein halbes Jahrtausend näher an das Original herangerückt, mit eher grammatischen und marginalen, inhaltlich aber verblüffend geringen Unterschieden! |

|

|

|

|

“In the beginning was the Word...”: in the first Chinese translations of the Bible, Christian missionaries of the 17th and 18th century had good reason to choose the version “In the beginning was the Tao...”. Dào can mean logos – but also more than that.3 |

„Am Anfang war das Wort…“ - in den ersten chinesischen Übersetzungen der Bibel durch christliche Missionare im 17. und 18. Jahrhundert griff man nicht von ungefähr zu „Am Anfang war das Tao…“: Dào bedeutet auch Logos – aber eben nicht nur.3 |

|

|

|

|

A secondary meaning of the word dào (“say, tell, speak, define”) is certainly used in the first line of the Dàodéjīng by Lǎozĭ, in a sophisticated play of words: |

Sogar eine konkrete Nebenbedeutung des Wortes dào „sagen, aussagen, sprechen; definieren“ wird schon in der ersten Zeile des Dàodéjīng von Lǎozĭ verschmitzt als Wortspiel genutzt: |

|

|

|

|

道可道,非常道

Dào–

if you can define it, it is not the

eternal Dào. |

道可道,非常道

Dào– kann man es definieren, ist es nicht das

ewige Dào. |

|

|

|

|

Tao is also a feeling for the All-Oneness, for the sum of all natural laws. It is not without reason that (since the publication of Capra's Tao of Physics) distinct parallels have been recognized between modern quantum-theoretic interpretations of the universe and the final regularities as described by Lǎozĭ. |

Dào ist auch ein Gefühl für das All-Eine, für die Summe aller Naturgesetze; nicht ohne Grund sieht man seit Capras Tao der Physik immer deutlichere Parallelen moderner quanten-theoretischer Deutungen des Universums und der letzten Gesetzmäßigkeiten, wie sie von Lǎozĭ beschrieben werden. |

|

|

|

|

In a clear way, Lǎozĭ gives universally valid treatments of themes like the preservation of nature, the prevention of war, wise and responsible leadership instead of possession-oriented politics. He also shows a way for individuals in their daily lives and a natural way of solving problems – preferably even before they start to develop. |

Aber auch Themen wie Erhaltung der Natur, Vermeidung von Kriegen, weise, nachhaltige Führung statt Besitz ergreifende Politik behandelt Lǎozĭ ebenso unmissverständlich und zeitlos gültig wie individuelle Lebensführung und natürliches Lösen der Probleme – möglichst noch vor ihrer Entstehung. |

|

|

|

|

Lǎozĭ holds up an immaculate mirror to all violence, all striving for material possessions and all passion in general. Also, Hans and Sophie Scholl made a reference to Lǎozĭ in their resistance („Weiße Rose“ = “White Rose”) against the Nazi regime!4 |

Aller Gewalt, allem äußeren Besitzstreben, aller Begehrlichkeit schlechthin hält Lǎozĭ einen makellosen Spiegel entgegen; auch die Geschwister Scholl beriefen sich in den Flugblättern der „Weißen Rose“ gegen das Nazi-Regime auf Lǎozĭ4! |

|

|

|

|

Lǎozĭ's “three Treasures” of the right way are self-sufficiency 儉, modesty 後 and love 慈 – in the sense of feeling with your fellow creatures. It is not surprising that concurrences with the philosophy of a certain Jesus of Nazareth have been deeply analyzed, and it is worth noting that Lǎozĭ anticipated these teachings more than 400 years earlier... |

Lǎozĭs „drei Schätze“ des rechten Weges heißen Genügsamkeit 儉, Bescheidenheit 後 und Liebe 慈 – im Sinne einfühlender Nächstenliebe. Wen wundert es da noch, dass auch die Übereinstimmungen mit der Philosophie eines gewissen Jesus von Nazareth erschöpfenden Analysen unterzogen wurden, mit vielerlei Parallelitäten, die wohlgemerkt zugleich Vorwegnahmen um mehr als 400 Jahre darstellen… |

|

We have all heard the proverb “Every journey starts with a first step”, often without suspecting that it comes from the Tao-Te-Ching. Gott schützt die Liebenden [God protects those who love] is already contained in the sentence “Heaven will save you, protecting you with love.” (Chapter 67).5 |

Wir alle hörten einmal das sprichwörtliche „Jede Reise beginnt mit einem ersten Schritt“, vielfach ohne zu ahnen, dass es aus dem Dàodéjīng stammt; Gott schützt die Liebenden ist schon in „Wen der Himmel retten will, den schützt er durch die Liebe“ (Kap. 67)5 vorgegeben etc. |

|

|

|

|

Hermann Hesse knew why (at the end of Siddartha) he had the ferry man speak taoistic wisdom: in the symbol of the water, in the eternal river, in love as the highest good, in the way leading beyond hinduism and buddhism, towards the Eternal Mother. He wrote the book Siddartha some years after the death of his father, Johannes Hesse, who had been a protestant missionary in India and who had published a booklet about the Dàodéjīng entitled: Lao-tsze. Ein vorchristlicher Wahrheitszeuge. From that year onwards, first traces of Hermann’s Chinese studies can be found, for example in the fragment of his novel Das Haus der Träume [The House of Dreams]. |

Hermann Hesse wusste, warum er in Siddartha den Fährmann zu guter Letzt taoistische Weisheiten aussprechen lässt: im Symbol des Wassers, im Ewigen Fluss, in der Liebe als höchstem Gut, im Weg über Hinduismus und Buddhismus hinaus zur Ewigen Mutter. Er schrieb Siddartha einige Jahre nach dem Tod seines Vaters Johannes Hesse, früherer protestantischer Missionar in Indien, der immerhin eine eigene Broschüre über das Dàodéjīng publiziert hatte: Lao-tsze. Ein vorchristlicher Wahrheitszeuge; auch Hermanns erste Spuren chinesischer Studien finden sich seit diesem Jahr, etwa im Romanfragment Das Haus der Träume. |

|

|

|

|

From Jung to Jaspers, from Hegel to Heidegger, great learned men as well as poets and writers have studied Lǎozĭ. In an interview, Luise Rinser said that in dark times, neither Christianity nor Buddhism can help her, but “only the old Chinese philosophy of taoism”. Elias Canetti once said: “Taoism has always attracted me insofar as it knows change and approves of it, without reaching the position of Indian or European Idealism... It is the religion of the poets, even though they do not know it...”.6 |

Von Jung bis Jaspers, von Hegel bis Heidegger haben sich große Gelehrte ebenso eingehend mit Lǎozĭ befasst wie namhafte Schriftsteller: Warum gab Luise Rinser einmal in einem Interview zu ... ihr helfe in dunklen Zeiten weder das Christentum noch der Buddhismus, sondern „nur die alte chinesische Philosophie: der Taoismus...“?! Elias Canetti gab die Antwort: „Am Taoismus hat mich immer angezogen, daß er die Verwandlung kennt und gutheißt, ohne zur Position des indischen oder europäischen Idealismus zu gelangen… Er ist die Religion der Dichter, auch wenn sie es nicht wissen...“.6 |

|

|

|

|

We intuitively understand the legend of the Three Greats of eastern philosophy when tasting vinegar: Confucius found it sour, Buddha found it bitter, and Lǎozĭ still found something sweet in it...7 |

Wir verstehen intuitiv, warum in der Legende vom östlichen philosophischen Dreigestirn, beim Kosten von Essig Konfuzius ihn sauer, Buddha ihn bitter fand, Lǎozĭ aber auch dem Essig noch Süße abzugewinnen vermochte…7 |

|

|

|

|

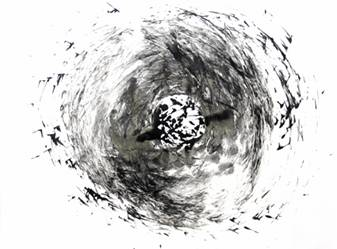

Drawings |

Zeichnungen |

| Our thanks go to Loni Liebermann for the wonderful drawings in the chapters! |

Loni Liebermann gebührt unser Dank für die wunderschönen Zeichnungen in den Kapiteln! |

|

Loni Liebermann, 2005

|

|